David Coulson, 55, did not see his family for the two decades he spent behind bars. But they were ready to welcome him home last month, starting with a surprise reunion.

On his fourth day of freedom, his adult son invited him to his grandson’s football game in Norwalk, California. He thought it would just be the two of them, but halfway through the game, Coulson turned around and saw his daughter, three grandkids he’d never met, and several other relatives.

“I was just bawling and torn up, and my daughter runs up and hugs me and is like, ‘You big ole crybaby!’” he said. “The grandkids accepted me with open arms. It was like I never left.”

For the last 20 years, Coulson was serving a life sentence with little hope of ever coming home.

His crime was stealing $14.

At the time of the 2002 offense, in which he took loose change from an unlocked garage, Coulson, then 35, was living on the streets of Long Beach and deep in the throes of drug addiction. He was also struggling with mental illnesses after surviving significant childhood abuse. Despite his documented health crises and having no violent crimes on his record, a judge ordered him to be locked up for life, saying he could only be considered for release after 35 years.

He was incarcerated under one of the US’s most extreme “tough on crime” laws, which aimed to indefinitely imprison “habitual offenders.” He only came home last month because a judge reviewed his case and declared that his punishment “shocks the conscience and offends fundamental notions of human dignity” and that he should never have been imprisoned at all.

Coulson’s release was unusual, but the extraordinarily harsh punishment he received was not. Experts say thousands like him remain behind bars in California, sentenced to life due to 1990s legislation, some of who may never be freed.

David Coulson’s mother was 16 when she had him; when he was four, she gave him up for adoption. Court records suggest that she was struggling with addiction and unable to care for him. “It was as if she said, ‘I don’t want you, you’re a piece of trash, lemme throw you away,’” Coulson recalled. “That might not have been her mindset, but that’s how I received it.”

He was adopted by a parks groundskeeper and his wife and grew up alongside six older siblings.

He was victimized throughout his childhood. He reported to the court and psychologists that his parents beat him, a brother would hit him “until he passed out,” and that he was sexually abused. His parents took him to a psychiatrist at a young age as he struggled with hallucinations and self-harm but eventually stopped his treatment. His family moved often; he attended seven different schools before high school, with no consistent special education.

“No one cared what happened to him,” one of his advocates wrote in a report summarizing his youth.

He later had two children but was in and out of their lives. He went to jail and prison for minor offenses in his 20s, including twice removing a window screen for a possible break-in but not entering the homes. He was living out of a tent by a freeway when he committed his final offense in 2002, walking into a residential garage that was open. Police and court records say he grabbed miscellaneous items, including a handful of coins from a jar, when a resident appeared.

Coulson left, and the resident chased after and tackled and punched him. Coulson dropped what he’d taken and fled. When police found him, he had in his pockets $14.08, which court records say was made up of quarters, dimes, nickels, and three pennies, and a “small, inexpensive digital scale.”

He immediately knew he might never walk free, thanks to a recently passed law: Three Strikes And You’re Out.

California adopted Three Strikes in 1994 amid a nationwide panic about crime, fueled in part by the kidnapping and murder of a 12-year-old girl in the state. The law established life sentences for any felony if the defendant was previously convicted of two felonies classified as “serious” or “violent.” Proponents said the law would “keep murderers, rapists, and child molesters behind bars, where they belong.” Instead, within a decade, nearly 3,500 people were given life sentences for nonviolent offenses such as shoplifting or drug possession.

“People were ripped out from their communities and never returned,” said Amber-Rose Howard, executive director of Californians United for a Responsible Budget, which works to reduce incarceration. “Folks with strikes began to live in fear that any mistake, or being in the wrong place at the wrong time, or being targeted by police, could wind you up in prison for life.”

None of Coulson’s crimes involved physical harm, and all of them, he said, stemmed from his addiction. But his final offense was prosecuted as burglary and robbery – two more strikes.

Coulson said he felt hopeless: “I was crying out for help. I was doing whatever I could to get the attention I needed. I was praying it wouldn’t end up with me in prison for the rest of my life, that someone would come to me and say, ‘What’s going on? What’s making you act this way? Why are you the way you are?’”

After his third-strike arrest, a psychiatrist diagnosed him with schizophrenia, and the courts deemed him incompetent to stand trial, sending him to a state hospital instead. But after he was medicated, the courts said he had “regained his competence,” and he was brought before a jury and convicted.

At his 2006 sentencing, the judge acknowledged his hardships: “I certainly wouldn’t want to have lived a childhood that Mr. Coulson had to live,” but added: “He’s just committing one burglary after another … He’s been given a number of opportunities, and he just hasn’t learned.” The judge gave him 35 to life, meaning he’d first be eligible for parole in 2032 at age 65, and ordered him to pay $10,020 in fines and fees.

“A life sentence was a death sentence to me,” Coulson said.

In prison, Coulson worked in the kitchen, ensuring there were halal options for Muslim residents like him, and trained others in prison jobs. He also participated in therapy groups that helped him grapple with his childhood trauma and facilitated “affirmations” workshops. Men would repeat the disparaging messages that had long been drilled into them (“I hate that I had you, you’re not worthy.”) and then replace those words with affirming comments (“You’re the best, I’m glad you’re here.”). “They’ve had all this trash bundled up in them, and they were able to let that poison out and replace it with positivity,” Coulson said.

Those experiences made him question why he never got any help on the outside: “All my cases were the same, but nobody asked me why I was using drugs or put me in rehab. It was just jail, jail, jail … People need help, but you put them away and create monsters in prison where people are in survival mode.”

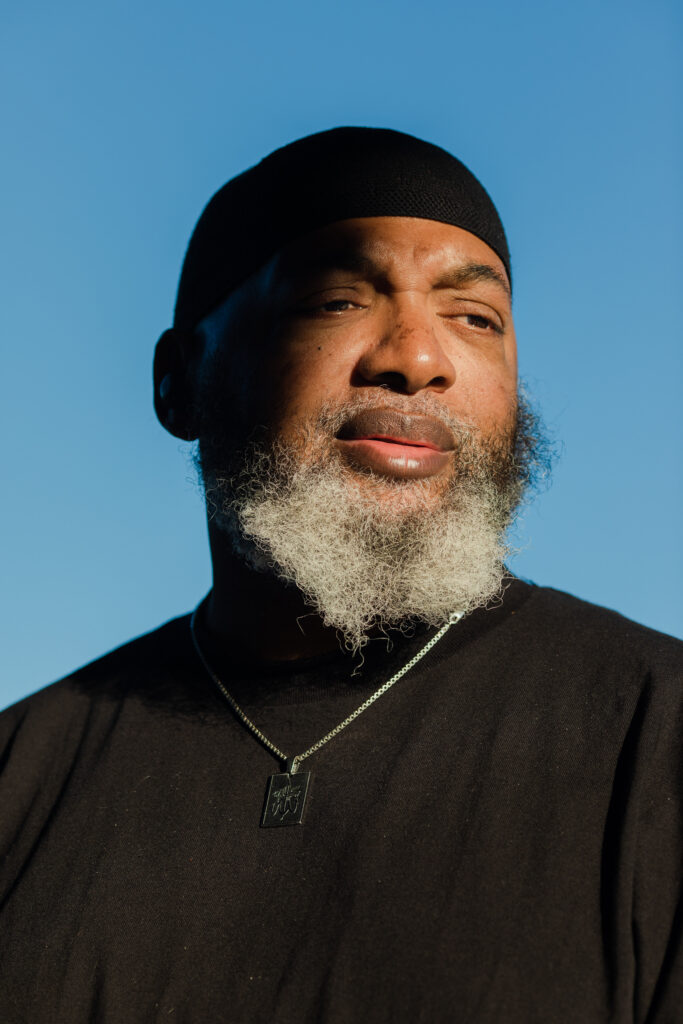

David Coulson, 55, with his wife, Veronica Nezey, shortly after his release from prison.

“That’s what’s broken with the judicial system – they don’t ask you, what’s your trauma?”

While in prison, he also reconnected with a childhood friend, Veronica, who is now his wife. Still, he expected to die in prison, especially during the pandemic when he got Covid.

But in August, California’s department of corrections and rehabilitation recommended that Coulson be re-sentenced, recognizing his achievements in classes and frequent volunteer work. Judge Daniel Lowenthal agreed and told Coulson at a 13 September hearing: “I’m shocked and angry at how you were treated by the system.”

Lowenthal compared Coulson’s trajectory to a white defendant who was the same age and also sentenced in Long Beach in 2006. That defendant had at least four prior violent convictions, including domestic violence, and his final offense was assaulting a Latino officer while using slurs. He got three years in prison. Lowenthal said an appropriate sentence for Coulson would have been probation and treatment, but now he should walk free with no conditions.

In the courtroom, Coulson wept: “This is all I’ve ever wanted in my life. I’ve been crying out for help all my life, and no one has ever heard me. Finally, somebody has heard me.”

The Three Strikes law – versions of which were adopted in 23 other states and in federal law – contributed to the explosion of California’s prison population and an overcrowding catastrophe. More than 33,000 people remain incarcerated under the law today, and 45% of people serving life sentences due to Three Strikes are Black despite Black residents making up just 6.5% of the state.

Research has found no evidence that the law reduced crime rates or deterred violence.

“It has no public safety benefit,” said Mike Romano, director of the Three Strikes Project at Stanford law school, who serves on a state committee that recommended Three Strikes be repealed last year. “By design, the law has targeted crimes of poverty, like small-time robbery, burglary, breaking windows, purse snatching.”

The sisters of the 1993 kidnapping victim whose case helped inspire the law have also called for its repeal, recently telling the Guardian, “We don’t want our pain to be used to punish anyone else.” (Repealing the law would require a ballot initiative.)

For now, Three Strikes remains on the books. A major 2012 reform established that “non-serious” and “non-violent” felonies would no longer count as third strikes, and an estimated 3,000 people have since been released. But that still left many people behind, including Coulson, because state statutes classify a wide range of low-level crimes as serious and violent even when little or no harm has occurred. And many “three strikers” who did commit violence have been imprisoned for decades.

“Keeping people in when they are 50, 60, 70 years old makes no sense and is cruel,” said Kate Chatfield, an advocate with the Wren Collective, a social justice group. “If somebody is not a public safety risk, it’s just punishment for punishment’s sake.”

In an interview with the Guardian, Lowenthal, the judge, noted that California had rolled back some of the harsh and racially disparate sentencing policies in an effort to end extreme punishments moving forward. But he said he would like to see the establishment of courts dedicated to retroactively reviewing imprisoned cases: “We should re-examine, with the same sense of urgency, the sentences imposed during our justice system’s period of excess.”

He could not comment on Coulson’s case but said, “When I learn of an unjust sentence that I believe doesn’t recognize the dignity of that person, it breaks my heart, and I lose sleep. There’s nothing more important and impactful than being able to rectify that.”

The Anti-Recidivism Coalition (ARC), a group that offers re-entry services, picked up Coulson from his northern California prison and has helped him get settled. A group called Mass Liberation is housing him for his first months home, and in recent days took him to buy new clothes and sort out ID documents.

He has been capturing photos of every moment on his new smartphone, which in two weeks filled up with images of his family hanging out in Long Beach. He’s still figuring out how to use QR codes and what web “cookies” are. His first meals at home were seafood: calamari, lobster quesadilla, and coconut shrimp. He said that being around people who aren’t incarcerated feels strange, noting how people bump into each other in public in ways that would never happen behind bars.

His wife, Veronica, said she was so overwhelmed when she hugged him for the first time she couldn’t speak. “I want him to feel his freedom. I want him to take time and smell the roses and wiggle his toes in the sand.” As the two of them walked through an LA rose garden on a recent afternoon, they took selfies, and he sighed as he held her, saying, “This is all I wanted.”

Coulson’s taking things day by day, but his dream is to go back into prisons – to support people who have been crying for help, waiting for someone to hear them.

From voting rights to climate collapse to reproductive freedom, the stakes couldn’t be higher in the coming midterm elections.

Politicians who spread lies and sought to delegitimize the 2020 election are pursuing offices that will put them in control of the country’s election machinery. Other assaults on essential liberties, from a record number of book bans to strict abortion bans, are proliferating at the local and state level. This picture is made all the more urgent by a supreme court that is enforcing its own agenda on everything from guns to environmental protections – often in opposition to public opinion.

With so much on the line, journalism that relentlessly reports the truth uncovers injustice and exposes misinformation is essential. We need your support to help us power it. Unlike many others, the Guardian has no shareholders and no billionaire owner. Just the determination and passion to deliver high-impact global reporting, always free from commercial or political influence. Reporting like this is vital for democracy, for fairness, and to demand better from the powerful.